On the afternoon of April 5, four New York real estate dignitaries rose from their pews at Temple Emanu-El — the mammoth synagogue built on the site of William Astor’s Fifth Avenue mansion — to eulogize the late 102-year-old developer Leonard Litwin.

Donald Zucker, Larry Silverstein, Steven Spinola and Gary Jacob spoke of a man of enduring courage, generosity and discipline, whose life was given to work, charity and his family.

They also talked shop.

“Let me tell you about some deals I did with Lenny,” Zucker, 86, told the hundreds of people in attendance from the lectern. The developer recounted a failed bid to buy a First Avenue building site from Con Edison. In another anecdote, Zucker recalled a time when the two of them traveled with their wives to Paris, where Litwin was unable to enjoy himself, telling his confidant that he received no pleasure in being away from his work.

Silverstein, 85, noted that Litwin had been an instrumental adviser on plans for one of Silverstein’s own apartment buildings. He extolled the late developer’s courage in building 10 Liberty Place, the first downtown luxury rental project constructed after the Sept. 11 terrorist attacks.

Spinola, who served as the powerful Real Estate Board of New York’s president for nearly three decades, remarked that Litwin’s company, Glenwood Management, had defied convention by building larger apartments than most other developers.

None of the four men, including Glenwood’s executive vice president, Jacob, said much about the political battles Litwin and his associates fought with their checkbooks for decades so that their red-hot building streak would never be interrupted.

“His passing was the end of an era,” New York lobbyist Suri Kasirer said of Litwin’s political spending. “Certainly, Lenny Litwin was one of a kind. There were not many people in real estate who were willing to come out as strongly as he did.”

Litwin’s peers in the business acknowledge that he wanted to help shape the ground rules for New York real estate through political contributions. But many downplayed the importance of the one man — whose company is considered the most prolific campaign donor in state history — in the context of the industry’s lobbying efforts.

“There are plenty of big machers,” said Peter Hauspurg, chairman and CEO of the commercial real estate brokerage Eastern Consolidated, who did seven land deals with Litwin. “There’s plenty of money to fill the space.”

The quiet kingmaker

The son of Harry Litwin, a poet and gardener, and Gertrude Litwin, Leonard Litwin [TRDataCustom] took on two public personas during his nearly 70 years in the business. In one of them, “Mr. Litwin,” as many of his peers called him, was the quiet and humble mastermind behind one of New York’s most admired luxury real estate empires. Glenwood, which Litwin founded in 1961, has developed more than 25 buildings and 8,000 rental apartments in Manhattan, many of them featuring large fountains and semicircular driveways with porte-cochères that mimic the old-money mansions of Long Island. Most are christened with Anglophilic names such as the Brittany, the Barclay, Hampton Court and the Somerset.

As Litwin’s fortunes grew — eventually landing him on Forbes Magazine’s list of billionaires in 2006 — he retained an incorruptible modesty and a quiet but piercing approach. Despite his small frame and soft voice, a few pointed words from Litwin could silence the crowded boardrooms of shouting Manhattan dealmakers.

And as a magnate with no Manhattan office, Litwin worked out of an undistinguished Chevy or in the ground-floor leasing office of one of his many Upper East Side buildings. He never hired a driver, instead commuting from Long Island to attend meetings and tend to his menagerie of skyscrapers until he retired from the business at the age of 98.

Well into his 90s, Litwin had his hands in the bushes. Many observed him instructing the landscaping staff, sharing skills he had cultivated long before gasoline-powered hedge trimmers had been invented. Litwin also devoted time and money to building charitable causes from the ground up. He and Zucker, one of his closest allies in the business, founded the Litwin-Zucker Center for the Study of Alzheimer’s Disease and Memory Disorders in Manhasset, Long Island, in 2004.

“He never wanted publicity, never wanted it to be known that he supported any charity or cause,” said Michael Stoler, managing director at Madison Realty Capital. “He gave voluntarily.”

But there is the other side of Litwin — the side that more often defined him in the public eye: his role as the “Duke of York,” according to his friends and colleagues. The nickname was a reference to the stately towers he fathered on York Avenue, and perhaps also an acknowledgment of the immense political influence he wielded. Litwin died at his home on April 2 as the most prolific bankroller of New York’s elected officials in its history. And by several accounts, not one who took his money was spotted at his funeral on Manhattan’s Upper East Side.

In the last five years of his life he was regularly outspending the Dursts, Rudins and Resnicks to preserve and change policies to ensure his company’s success. Republicans and Democrats, Manhattanites and Buffalonians all received donations, but in most cases not from Litwin himself.

Instead, the developer and his associates gave with astonishing frequency using dozens of shell companies, exploiting a loophole in campaign finance laws that allowed them to give exponentially more to candidates than they would otherwise be permitted as individuals. An analysis of those donations by The Real Deal and ProPublica at the end of 2016 found that Glenwood had donated at least $9 million to New York State candidates since 2000 using limited liability companies with names like River York Stratford LLC. That didn’t count the money given to political action committees, or to city officials and candidates running for national office. While other major real estate donors —Related Companies’ Steve Ross and the Durst Organization’s Douglas Durst among them — have similar interests and comparably large (or larger) companies, none come close to giving as much as Glenwood.

Yet even though Litwin was well known for his generous political donations over the course of several decades, the extent of Glenwood’s lobbying operation wasn’t fully realized until the public trials of two ex-politicians: former state Assembly Speaker Sheldon Silver and former state Senate Majority Leader Dean Skelos.

Litwin and his associates were never formally charged with any wrongdoing (one, Charlie Dorego, Glenwood’s general counsel, received immunity for cooperation). Testimonies and evidence presented in the cases, however, revealed a meticulous and sophisticated lobbying apparatus that operated both internally and via major trade groups, including REBNY and the Rent Stabilization Association. Through that disciplined system Glenwood often pushed its own agenda on the 421a tax exemption, New York City rent regulation and campaign finance reform, among other issues.

John Keahny, director of the anti-corruption group Reinvent Albany, described Litwin as an “Oz-like figure” behind Glenwood’s elaborate influence machine.

“Litwin was probably a man of many parts,” Keahny told TRD. “But sadly, we remember him as a guy who seemed to [believe] that money buys everything — including government.”

More than a century

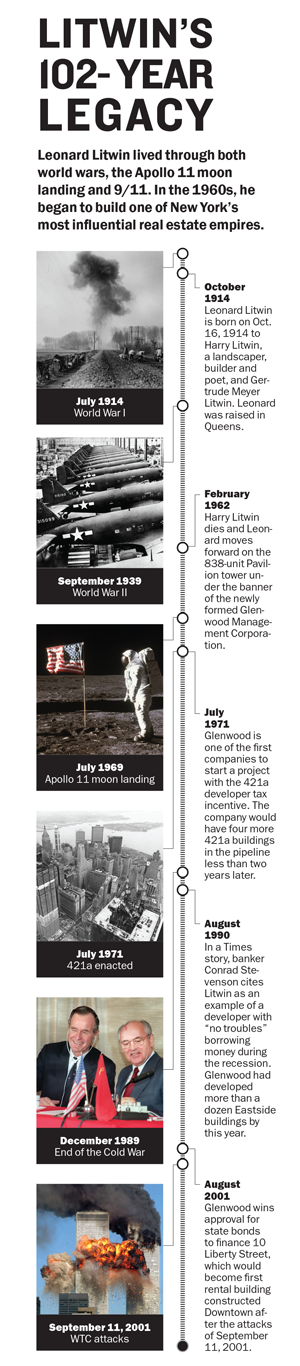

Leonard Litwin was born on Oct. 16, 1914, in the same week that the U.S. enacted the Clayton Antitrust Act and the Sarajevo trial began for the assassination of Austrian Archduke Franz Ferdinand.

Litwin’s father, Harry, an immigrant from Ukraine, owned a nursery in Melville, Long Island, and worked as a landscaping contractor for buildings in the New York metropolitan area. He also penned poetry under the name Harry Woodbourne and in the 1950s published a collection of his works, “The Green Kingdom” — Harry’s father was reportedly Czar Nicholas II’s private forester.

At the end of World War II, Harry and Leonard ventured into development, and in 1949 they broke ground on a 56-unit garden apartment building for working- and middle-class class residents in Freeport, Long Island, the New York Times reported at the time. Once out on his own, Leonard tried his hand at Manhattan co-ops but eventually swore off them, according to those who knew him, preferring the stability and control that came with rental ownership.

Harry died in 1962, during the construction of the Pavilion, an 838-apartment building at 500 East 77th Street, near York Avenue. Leonard, who was 50 years old at the time, completed it for his father in 1964. From then on, he developed almost nothing but rentals for the rest of his career.

“We built in a world that doesn’t exist today, when there were five or six builders in Manhattan. ” Zucker told TRD. “Now there are more than 50.”

Litwin’s career almost seemed immune to adversity — at least on the surface. A banker who spoke to the Times for a 1990 article about the business woes of Donald Trump cited Litwin as an example of a developer with “no troubles.”

But city and state politics would get in the way from time to time. In 1969, the city threw a curveball at landlords and a lifeline to tenants: rent stabilization. With that came the creation of the Rent Stabilization Association — then the real estate industry’s self-regulator for the new program of government-mandated rent caps. Litwin was an active member of the early RSA, according to Morty Matz, who worked in public relations for the group in the 1970s and ’80s.

“Lenny was a very involved, very focused person,” said Matz, 93, who has lived in one of Glenwood’s prominent Upper East Side buildings for nearly two decades.

Tenant activist Mike McKee, then of the Tenants and Neighbors Coalition, remembered Litwin as a prominent public advocate of city landlords in those days, as the RSA was undergoing a major transformation. The group had been the subject of actions brought by New York Attorney General Robert Abrams for noncompliance with its duties under the rent stabilization laws. That led to the legislature bringing rent regulation back under the auspices of the state in 1985, which allowed the RSA to become the full-fledged lobbying group and trade association it is today. Though never the group’s public face, Litwin was a mainstay at RSA through thick and thin, and it was here that his reputation as the man behind the curtain began.

“My sense is he was a sheer pragmatist, focused on the bottom line,” McKee said.

Litwin also helped bring REBNY and RSA together into a more congruous real estate lobbying bloc, combining forces and bank accounts to tackle real estate policy in Albany and at City Hall, Spinola recalled.

“One of the things that Lenny stressed over and over to me and to Joe Strasburg, the head of RSA, was for us to be working together,” he said. “I think he recognized that an industry could help shape policy and direction for the city of New York if it was united in organizations.”

Building lobbying power

Over the years, Litwin saw how one policy could determine whether someone wins or loses in the Manhattan development game. Then in 1971, Glenwood became one of the first real estate firms to get a boost from a new tax exemption for residential construction: 421a. That quickly turned into the largest rallying point for the company’s campaign-finance operation for the next four decades, according to sources.

In those days, Litwin did not rank among the rest of the well-heeled NYC real estate crowd when it came to campaign donations. His giving, for example, did not make the list of top donors to John Lindsay’s 1969 mayoral bid, which included the likes of Harry Helmsley and other industry titans. Even two decades later when the Buffalo News did an analysis of top state-level givers, Litwin came in at just a total of $11,000 given between 1989 and 1990 — high for those years, but a drop in the bucket compared to where he would go. It was around that time, however, that Litwin’s political dealings began to receive more scrutiny in the press.

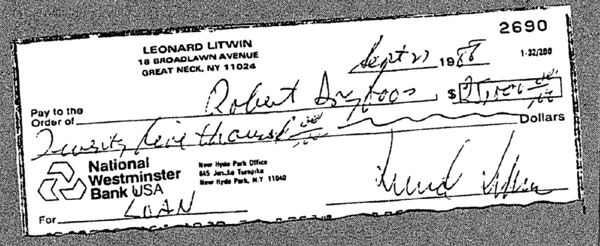

In the late 1980s, a $25,000 check written to City Council member Robert Dryfoos was criticized when it came to light that Dryfoos had given an impassioned speech in favor of applications to rezone a former animal shelter for a high-rise Glenwood development. Months after the rezoning was approved, Litwin wrote Dryfoos the check personally, indicating that it was a “loan,” in an apparent violation of ethics rules. Records reviewed by the Times in 1991 showed that Dryfoos had mysteriously stopped paying bills at a Glenwood-owned parking garage on East 74th Street. Neither Litwin or Dryfoos, who was also facing damaging accusations of tax evasion, was ever formally charged with wrongdoing, but the councilmember opted not to seek re-election. Meanwhile, the LLC that owned the garage where Dryfoos was reportedly parking for free went on to make at least 54 unique donations, totaling more than $493,000, to state and city politicians and political groups between 2006 and 2016. Notable recipients include Andrew Cuomo and REBNY’s Jobs for New York PAC.

Litwin wrote a personal check to City Council member Robert Dryfoos in the late 1980s as a $25,000 “loan.”

During the Silver trial, which lasted for less than five weeks, Glenwood employees and lobbyists explained to prosecutors how the company’s LLCs were mobilized to give to candidates who supported extended tax benefits and favorable rent laws and at the same time enhance Republican strength in Albany. The trial further exposed how Silver received hundreds of thousands of dollars in kickbacks from a tax certiorari firm he had asked Glenwood to give its business to — a key component leading to Silver’s conviction.

The level of Glenwood’s access to politicians and policymaking came as a shock to even veteran members of the tenant movement, including Legal Aid Society attorney Judith Goldiner, who says it helped explain why Silver had turned his back on pro-tenant causes, culminating in the Rent Act of 2011, which saw the renewal of 421a and did not bring an end to vacancy decontrol as they had hoped.

“We thought it was more about RSA and REBNY, and the money that was getting funneled in that way from lots of landlords, and I don’t think we really understood quite the magnitude of what was going on,” she noted.

Many have suspected that by the time the trial was underway, Litwin was not in good enough health to understand what was going on. After the complaint against Silver was brought by then-U.S. Attorney Preet Bharara in January 2015, Glenwood’s political giving became a shadow of its former self. It went from being the largest political giver in the state, with more than $1 million in donations in 2014, to giving candidates and committees less than $67,000 in the first half of 2015 and just over $51,000 in all of 2016, which was an election year.

A drive to “build forever”

All in all, Litwin’s peers in the business say his passion for real estate underscored everything else.

“I never had the sense that Mr. Litwin was either a Democrat or a Republican,” said Mary Ann Tighe, CEO of the tri-state region at CBRE and a colleague of Litwin’s at REBNY. “I think that all of it stemmed from his desire to keep building the next building.”

Zucker claimed that in his half century of knowing Litwin, the two never discussed politics, but when asked if the motivation to give stemmed entirely from state and local real estate policies affecting taxes and rent laws, he replied: “Probably all of those, probably all of the above.”

Jeffrey Gural, the chairman of Newmark Grubb Knight Frank, recalled that Litwin often had his mind set on bigger-picture national issues, especially ones that resembled those he fought for at home. “Lenny’s biggest issue was he wanted to see the estate tax go away, which is very understandable when you’re as wealthy as he was,” Gural noted.

As for Glenwood, the company has already learned how to function without Litwin, who spent the last four years of his life on a farm in Melville. The company is now run by long-time executive Jacob and at least three of Litwin’s family members, including his daughter, Carole Pittelman, who is lauded by many at REBNY as the brains behind many of the company’s developments. Jacob has been with Glenwood since 1973 and oversaw one of the rarest transactions for the company in 2016: a property sale. Glenwood sold the Hamilton, a 265-unit Upper East Side rental, to the privately held investment company Bonjour Capital for $150 million. Jacob and the Litwin family declined to speak for this story.

In 2013, the company gave hints as to which direction it may be headed in when it planned a boutique condo building with a $20 million penthouse at 60 East 86th Street. The decision, it was reported at the time, was made by Litwin’s grandsons, Steven and Howard Swarzman.

Litwin’s funeral at Temple Emanu-El drew hundreds of people, including some of the biggest names in New York real estate. Yet no political figures were sighted at the service by those who spoke to TRD.

Jacob recently told Commercial Observer that the firm is also pursuing 100 percent affordable projects, calling it “a new focus.” But several who have known the company business model for years told TRD that they expect Glenwood to keep on with its pattern of one sky-high luxury rental after the other.

Tighe, for one, said she thinks the firm will need to adapt to the times and the market. “If the profile is to continue to build rental housing, I think it’s going to be very, very hard to do,” she said, citing land prices among other factors limiting returns.

After real estate had its turn at the Emanu-El funeral service on April 5, Litwin’s great-granddaughter rose to recite a poem by the Victorian English utopian art critic John Ruskin, who believed in the power of art to elevate the poor. Evoking the many towers that will stand for years to come, she read: “When we build, let us think that we build forever.”